Elections, like most things, are increasingly moving Online.

- Nov 9, 2019

- 7 min read

Updated: Mar 24, 2021

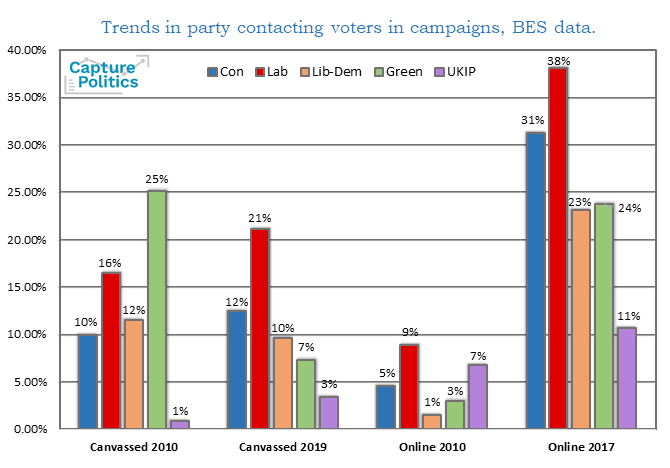

Using the #BritishElectionStudy election #data from the post wave surveys of #2010 and the #2017 election this analysis finds electoral competition is moving increasingly online. This can be said as more #voters recall they had been contacted by a party online in the 2017 General Election than compared to the 2010 election.

In 2010 around three-quarters of voters were contacted at least once by some method listed within the survey during the election. Most often this method was through a leaflet or letter being sent to the respondent’s home address. Online contact with parties’ campaign messages was much more limited with no party reaching over 10% of the electorate through a variety of online campaigning methods, such as through #SocialMedia and email. On top of this, #TelevisionInterviews, coverage by the television press, and reports by the written press were still more essential than online campaigning due to a combination of low contact rates and young people making up most voters who were online.

It is important to remember that #Facebook around the time of the 2010 election was mostly used by people born in the late 80s/ early 90s and therefore were either too young to vote, or unlikely to vote in large numbers. Therefore, there was little incentive for the parties to use a significant proportion of their limited campaign budget focusing on online advertising as the return of votes would be limited. However, by the 2017 #GeneralElection, Social Media had seen a significant upward trend in the number of people using such sites. Facebook users started to notice their parents, and sometimes even their grandparents, joining their once family free social space. As a result, a greater number of regular voters were all available in one space and one platform at any given time in an election campaign. Moreover, this platform had developed specialised #algorithms to capture, process, and understand their user’s data, allowing for more #TargetedElectionCampaigns than ever before.

It is important to recall in Pre-Social Media times a party would have to identify areas based upon demographics and get leaflets explaining their message to these targeted voters which can be costly and time-consuming. However, even targeted professional campaigns would still result in messages falling upon audiences parties were not targeting as even areas with distinct demographics still have many residents living in that area who are unlikely to vote for that party. For example, in pre-Social Media times if a party wished to target an area to promote a series of policies targeted to younger voters even when successfully identifying a neighbourhood with an average younger age group it would still deliver many leaflets to older people who may not be at all influenced by their campaign. However, Social Media platforms with large user databases can target younger people across a specific geographical space more effectively, and for less of the cost, than even professionally-led targeted activist and leafleting campaigns can do. As a result, it is not surprising that campaign spending and campaign time is increasingly focused on online campaigns. The #BBC has recently announced that the three largest parties have already spent £20,000 on Social Media targeted campaigns even before the campaign had officially started on the 6th of November 2019 (Sargeant 2019).

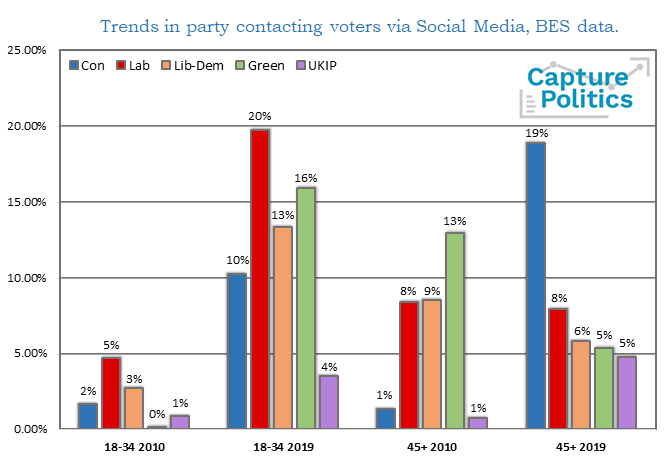

The BBC and the #Guardian also reported that this online spending was increasingly targeted to specific demographics per party spending. For example, the Labour Party had disproportionately targeted younger groups, whilst the Conservatives had disproportionately targeted advertisements to older groups (Waterson 2019, Sargeant 2019). This raises the questions of is the rise of online campaigning healthy for democracy, or does it encourage parties to focus more on their own bases and provide fewer incentives to reach out to a more diverse group of voters?

According to the British Election Study (BES) the increase in online campaigning, which voters can recall in post-election surveys, has not led to an increase in the number of voters contacted during a campaign for all the parties. Some voters may have not been contacted by certain parties as their online campaign had filtered them out of their campaign whereas a leaflet or an activist door-knocking campaign might have included them. The efficiency of Social Media databases may allow parties to more directly contact voters they think might positively respond to their message, yet it might also cause fewer voters to be contacted. This may lead to parties being no more able to fulfil their role as representatives and responders to voters than compared to pre Social Media times. It could potentially even make parties less responsive.

It may make them less responsive as it may cause parties to become ever more focused upon narrow echo chambers that support their views as they know this type of campaign will be better value for money and will contact voters they can win over. As a result, campaigns might become more targeted at specific groups and be less focused on representing a broad coalition of voters. Analysis from the BES on voter’s responses to if they felt they were, or were not, contacted on Facebook during the election shows such a trend.

In 2010 due to the low contact rates and fewer targeted campaigns online parties mostly contacted few voters from all age groups through online methods. However, by 2017 respondents to the survey showed clear diverging demographic trends in which parties had contacted them through this Social Media platform. Younger age groups recorded they recalled being contacted by Liberal and Left parties, whilst older people were contacted by Right-wing parties, such as UKIP and Conservative, at a higher rate. This was also a similar trend for groups with different level of qualifications. Groups who stated they had Degree, or above, qualifications were much more targeted by the Liberal and left parties of Labour, Liberal and Green than compared to groups with lower-level qualifications who were mostly targeted by Conservative parties.

There is some evidence that these Social Media campaigns might have helped parties increase their vote share. For example, those who reported they recalled seeing Labour Social Media campaigns were more likely to vote Labour and less likely to vote Conservative. There was the opposite trend for those who recalled seeing Conservative ads online. These effects are not statistically significant in the linear regression analysis, displayed above, which perhaps suggests that Social Media ads may not determine votes, but correlate with party support. In other words, people who decide to vote for Labour might recall seeing Labour adverts online as it reaffirmed their beliefs and opinions rather than changing them. However, it could equally be argued that these ads may have increased support amongst those who saw them. The results showed that Labour targeted younger voters and from the regression analysis it can be seen those who saw Labour’s ads were more likely to vote for them. Therefore, the generational divisions in the election may have been reinforced and partly created by Social Media trends and campaigns. Crucially, it must be noted that more in-depth studies, such as lab experiments, need to be conducted in order to analyse the effectiveness of Social Media campaigns before they can be said to affect election outcomes or not. However, as long as politicians believe they do then campaigns will continue to move online.

Conclusions

Overall Social Media is probably not causing these divisions as these divisions mostly pre-date these groups joining Social Media, however, Social Media may be exacerbating such divisions. As Social Media platforms acquire ever larger databases and more sophisticated algorithms, which will be increasingly geared towards improving advertising targeting methodologies, political parties understandably will increasingly move more of their campaigns online at each election cycle. These technological developments will allow for larger campaigns to target voters parties are specifically after for a better price than older campaigning methods allow for. As parties target their own base at a greater rate than before it could lead to parties being less responsive and representative over the long-term. In the UK where there is a winner takes all model this might cause parties to double down on their bases as not getting these votes can be the difference between achieving great power or almost none at all at the election. As a result, the party system may begin to become more polarised and this, in turn, might make it harder for parties to broaden their appeal, making it harder for parties to represent and respond to a majority of voters. This in turn could create a vicious cycle where the voters are split along the left and right bloc based around divided demographics which would make the UK more polarised, unstable and harder to govern.

With this election occurring during the shortest days of the year the opportunities for traditional campaigning methods, such as canvassing, will be more limited than in previous elections. Consequently, parties towards the end of the campaign may increasingly need to turn to online sources to be able to reach the voters they want to communicate with. Therefore, Social Media will likely be talked about in the aftermath and debates about its influences, good or bad, will likely not go way in the near future. Indeed during the creation of this article stories have been published highlighted questions of Social Media's problems when it comes to keeping election free and fair (Doward 2019, Syal 2019).

Writer - James Prentice, Sussex PhD politics researcher, first published: 09/11/2019.

References used:

Sargeant, P. (2019). General Election 2019: Who Have Parties Been Targeting on Social Media? - BBC News [Online]. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-50335567 [Accessed: 9 November 2019].

Syal, R. and Waterson, J. (2019). Tories accused of using public funds for Facebook ads in key seats. The Guardian [Online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/nov/01/tories-accused-of-using-public-funds-for-ads-on-facebook-in-key-seats [Accessed: 9 November 2019].

Waterson, J. (2019). Facebook: we would let Tories run ‘doctored’ Starmer video as ad. The Guardian [Online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/nov/07/facebook-we-would-let-tories-run-doctored-starmer-video-as-ad [Accessed: 9 November 2019].

Data used:

Fieldhouse, E., J. Green., G. Evans., H. Schmitt, C. van der Eijk, J. Mellon and C. Prosser (2017) British Election Study Internet Panel Wave 13. DOI: 10.15127/1.293723. Dataset found: https://www.britishelectionstudy.com/data-object/wave-13-of-the-2014-2018-british-election-study-internet-panel/

Comments