Labour’s lost decade: Why has Labour lost the last four elections?

- Capture Politics

- Nov 17, 2020

- 5 min read

Updated: Mar 25, 2021

This blog outlines how the main reasons behind Labour's electoral problems.

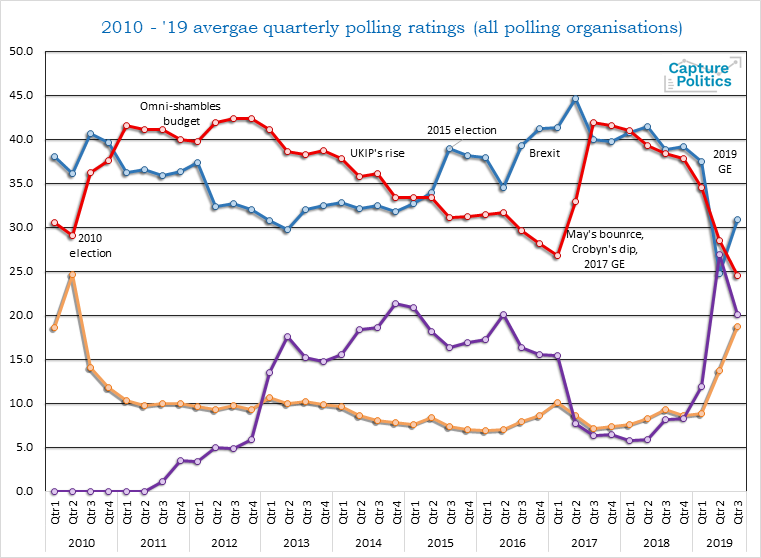

“As the decade progressed these centre-ground parties were greatly altered. Initially, the Conservatives found themselves being dragged into positions UKIP owned”

Labour’s defeat in 2019 marked its fourth successive election loss. Since then there has been much discussion amongst Labour, media and academic circles as to what the main reason behind this could be (Ashcroft 2020; Beckett 2020; Sobolewska and Ford 2020; Cutts et al. 2020; Goodwin 2019; Morgan 2019). Several theories have been proposed to explain the lack of competitiveness within British politics. This short blog piece will outline evidence that supports each theory and argues that the main reason why Labour keeps losing has been a combination of all the analysed factors.

The Leadership question

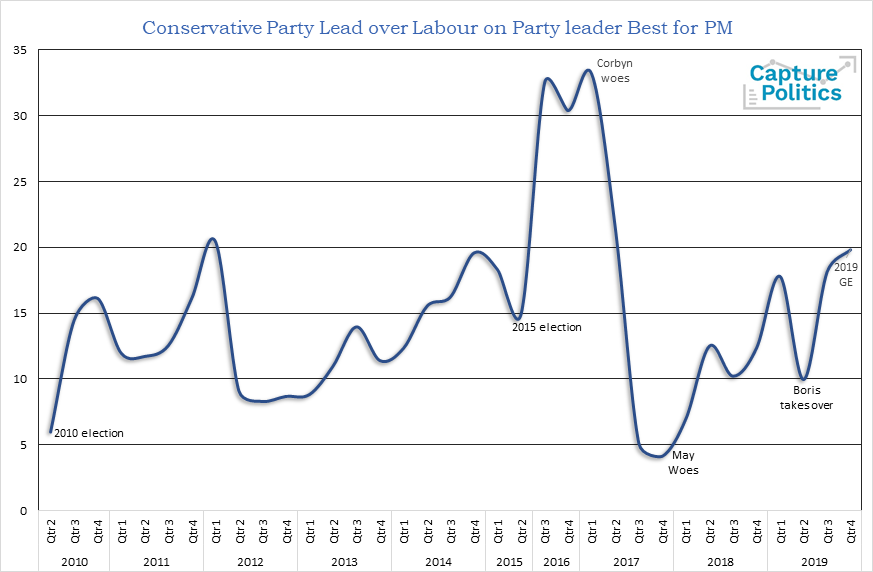

One argument as to why Labour has lost successive elections is that they are simply not presenting themselves in a way that can resonate with the majority of the country. This is symbolised through the leaders Labour has selected to represent their party, which according to polling data throughout the last decade failed to come across as more credible than the Conservative Prime-ministers (PM) of the last decade. Throughout the coalition, the Conservative leadership was rated much more highly than the Labour leadership were, and according to the British Election Study (BES) this was the case throughout the 2015 election also (Clarke et al. 2016). Moreover, going into the 2019 election Labour had a huge deficit to the Tories in leadership approval ratings, with over half the electorate preferring Boris over Corbyn. More worryingly for Labour other research has found Labour defectors thought Labour was offering leadership that was not just incompetent, but actually wanted to undermine what they saw as the nation’s identity and values (Mattinson 2020; Rayson 2020).

The Economic factor

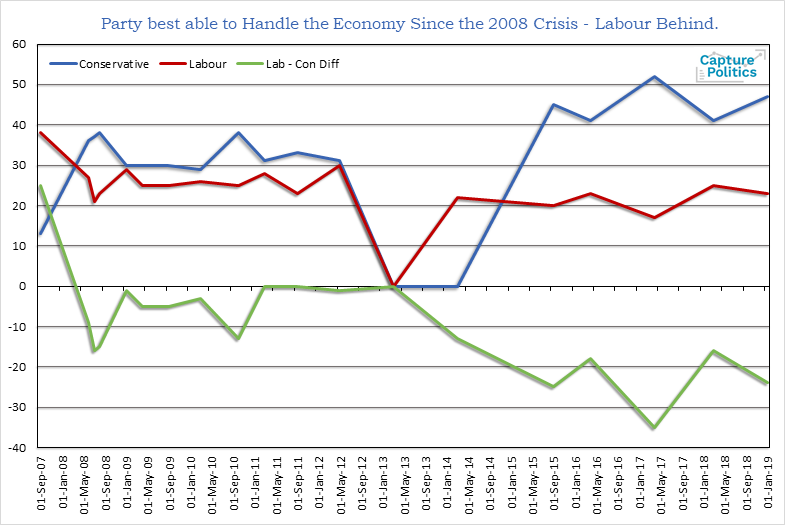

This theory is quite simple. Labour has long had a problem with convincing crucial swing voters that they can be trusted to run the economy and handle the public finances. Further to this, Labour is argued to have made this image problem worse by not being able to explain what they got wrong in the events leading up to the financial crisis. In particular, Labour has had a tough time convincing the public they can spend government finances wisely as they have not explained why a large deficit was allowed to have emerged before the financial crisis hit. This problem had been magnified in 2019 where Labour kept on adding spending commitments to an already ambitious manifesto. This especially became of great concern to swing voters Labour lost in 2019, many of whom reported in focus groups that they felt Labour had lost control and could not be trusted with their money (Mattinson 2020). Further evidence of Labour’s economic credibility issue can be found within polling data where Labour has been found to be behind the Tories in being the best party to manage economic affairs since the 2007/08 recession.

Not seen as credible on the biggest issues of the day

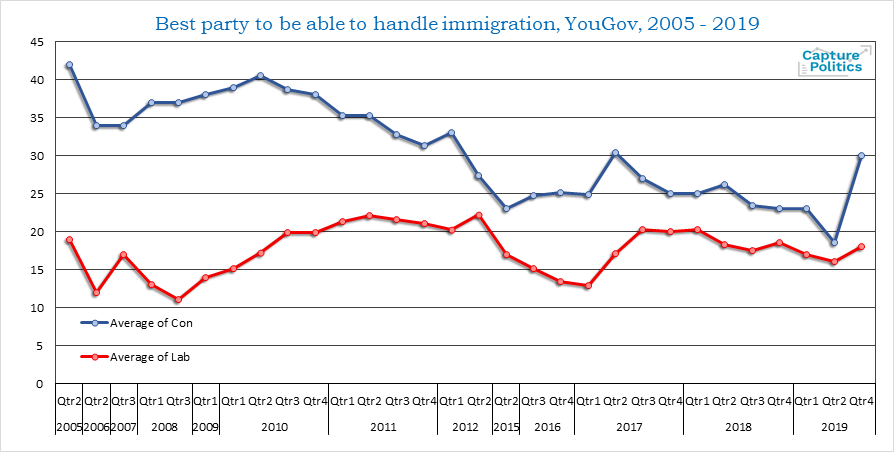

Another competing theory is that Labour’s credibility problem stretch much further than just the economic debate. The party’s credibility problem might stretch onto what has been, at least in the electorate’s view, the biggest issues, immigration and Europe. Labour has been behind in being seen to be the best to manage both of these policy concerns. Going into the 2015 election Labour was less trusted on migration policy than the Conservative and UKIP Party. Leading into the 2019 election Labour was significantly behind the Conservative Party on the issue of Brexit, with many more voters thinking the Tories were more able to end the Brexit debate. According to BES data Labour were particularly behind amongst voters who abandoned them for the Conservatives in 2019 on both the immigration and Europe debate.

The cultural problem – The electorate has realigned.

This leads us to the cultural problem Labour faces. The electorate has changed, and this has mostly favoured right-wing parties. This divide refers to the new education divide where highly educated younger students have congregated in University constituencies and moved away from areas without university access. This has left some traditional working-class towns to have ageing populations and declining skill levels. To make matters worse these areas have been most exposed to globalisation and de-industrialisation. This created a scenario where these towns suffer economic decline and do not have the demographics left in the area to make many possible solutions viable. As a result, these areas stay depressed, feel left-behind and ignored, which only gets worse as these areas fear the effects of immigration and Europe will make things worse. Liberal Left-wing parties like Labour are presented with a problem, these areas no longer believe voting Labour makes a difference and Labour do not represent their concerns on immigration or Brexit. Left-liberal parties cannot represent both sides, especially as their liberal membership refuses to compromise, their base fragments and their vote share goes down, which occurred with Labour’s Red Wall in 2019. Therefore, Labour has struggled to win due to these longer-term shifts which are hard to reconcile.

Conclusion

Overall the evidence has suggested Labour has struggled to win because they have made mistakes in the leaders they have elected and how they have presented them to the public. Moreover, they have failed to explain what economic mistakes they made and how they have learnt from them so they can be trusted with the public finances again. Further to this, Labour has not set out clear plans to how they would address the toughest issues of the day, such as immigration and Europe. Finally, there have been long-term shifts which have meant Labour has been unable to represent their traditional voters, who have concerns with Europe and immigration, alongside their newer base, who have more liberal values on such policy issues. This has led to a realignment that has increased Conservative support and decreased Labour’s. All these factors combining at the same time can go a long way in examining Labour’s lost decade.

Bibliography:

Ashcroft, Lord. 2020. Diagnosis of Defeat: Labour’s Turn to Smell the Coffee - Lord Ashcroft Polls. London: Ashcroft Polls. https://lordashcroftpolls.com/2020/02/diagnosis-of-defeat-labours-turn-to-smell-the-coffee/.

Beckett, Andy. 2020. ‘Can Labour Rebuild Its Red Wall without Losing Its Cities? | Andy Beckett’. The Guardian, 12 September 2020, sec. Opinion. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/sep/12/labour-red-wall-cities-lost-voters-liberal-values-.

Clarke, Harold D., Peter Kellner, Marianne C. Stewart, Joe Twyman, and Paul Whiteley. 2016. Austerity and Political Choice in Britain. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cutts, David, Matthew Goodwin, Oliver Heath, and Paula Surridge. 2020. ‘Brexit, the 2019 General Election and the Realignment of British Politics’. The Political Quarterly 91 (1): 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12815.

Goodwin, Matthew. 2019. ‘This Is One of the Most Seismic Political Realignments in Postwar History. The Tories Had Better Be Careful’. The Telegraph, 3 September 2019. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/politics/2019/09/03/one-seismic-political-realignments-postwar-history-tories-had/.

Mattinson, Debroah. 2020. Beyond The Red Wall. London: BITEBACK Publishing. http://www.vlebooks.com/vleweb/product/openreader?id=none&isbn=9781785906145.

Morgan, Piers. 2019. Piers Referees a Heated Debate Between Labour Factions | GMB. Video. Good Morning Britian. London: ITV. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KawAKTrk2No.

Rayson, Steve. 2020. The Fall of the Red Wall. London: Amazon.

Sobolewska, Maria K, and Robert Anthony Ford. 2020. Brexitland: Identity, Diversity and the Reshaping of British Politics. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108562485.

Comments